News & Updates

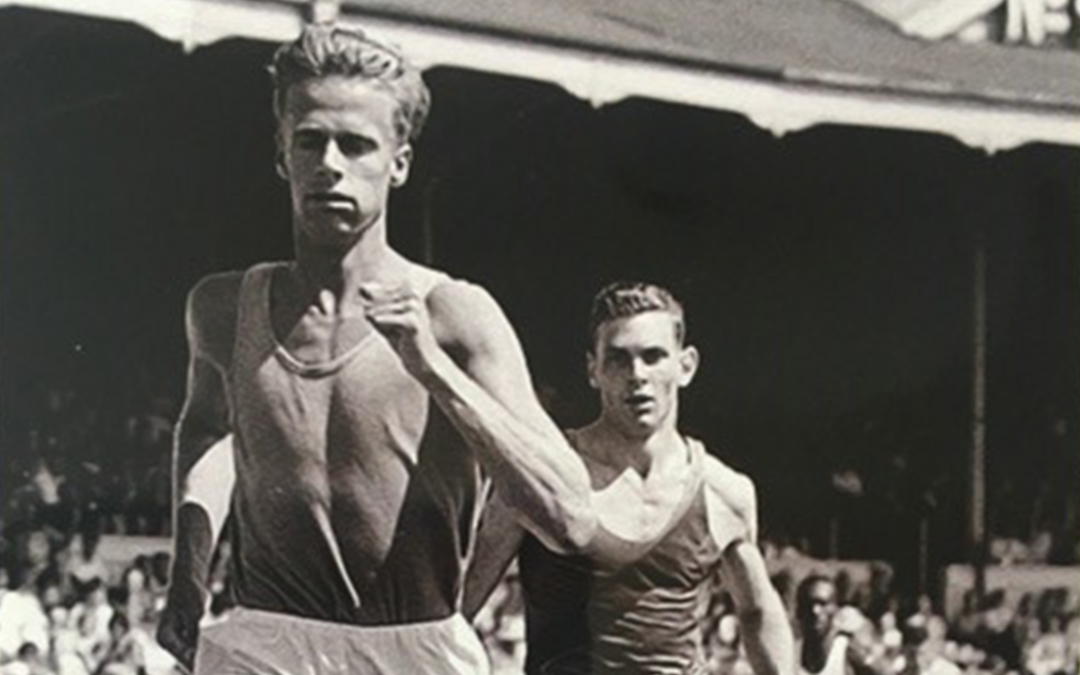

Pacemaker relives Sir Peter Snell’s epic world 800m record

(Photo: Sports Heritage Trust – Whanganui)

On the 60th anniversary of Sir Peter Snell’s world 800m record we toast the occasion by speaking to Barry Robinson, the man who helped pace the Kiwi sporting legend to his glorious time.

Perhaps few athletes if any have a greater understanding of what Sir Peter Snell achieved on Feb 3, 1962 quite like race pacemaker Barry Robinson.

That day the Kiwi middle-distance icon produced one of the greatest runs of his career to dismantle the world 800m record by the best part of a second-and-a-half at Lancaster Park, running a brilliant 1:44.3 (and 1:45.1 to break the world 880yd record).

To put the performance into context some 60 years later the time still stands as the New Zealand record, it would have been quick enough to have won all but two of the past six Olympic men’s 800m finals and remember this was on a damp, grass track long, long before the era of the super shoe.

It was a simply awe-inspiring display of speed endurance one which Barry, now aged 84, will forever be associated thanks to his job as pacemaker.

Born and raised in Auckland, Barry carved out a career as a sprinter/hurdler of some distinction. A four-time New Zealand 440yds champion and national 220yds hurdles gold medallist he competed internationally over one lap at the 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Cardiff, over 200m and 400m at the 1960 Rome Olympics, where he was room-mate of Peter, before later appearing at the 1962 Commonwealth Games in Perth.

Yet nobody was more surprised than Barry when just a few days out from the meet at Lancaster Park he received a call out of the blue from Athletics Auckland President and Chairman Frank Sharp requesting he act pacemaker to Sir Peter over 800m.

“Frank rang me, and I guess I would have been the obvious one to contact as I was the fastest 400m runner in New Zealand,” recalls Barry, who lives today in the Auckland suburb of St Heliers.

“I was told Peter was going to be running very seriously but there was no mention of a world record attempt,” adds Barry despite Peter setting a world mile record just days before on 27 January at Cooks Gardens in Whanganui.

“It was the first and only time I’d ever been a pacemaker and I’d never run a competitive 800m in my life,” he explains.

“Remember, those were the days when the pacemaker had to finish the race for the race result to be certified, so it presented a new challenge.”

Not only that, at no stage was their any discussion about a time split Barry should aim for at 400m – a planning process that seemed almost prehistoric compared to today when world records can be assisted by technology in which flashing computer-generated lights aid athletes with the precise speeds they should be running.

Despite the paucity of planning, Barry admits he was fully aware of Peter’s other-worldly form during the summer of 1962.

“Two or three weeks before I had seen Peter train down at the Auckland Domain,” recalls Barry. “I remember he ran non-stop a series of ten or 12 400m reps. Every alternative lap he ran in 52 or 53 seconds with the alternative recovery run in 65 seconds. What he did that night at the Auckland Domain was by far the greatest training session I’d ever seen. I remember thinking he was in superlative shape.”

Yet when Barry arrived in Christchurch on Friday – the day before race day – expectations shifted in his mind because of the steady rain in the city. A sodden grass track was no recipe for a world record.

“I thought the rain would destroy his chances,” adds Barry.

He woke up the next day to steady drizzle yet late morning the weather lifted and with the race due to start early afternoon, it was like a sign something special could be on offer.

“I thought it had been like a mission in redundancy on a damp, slow grass track but when I got there, two hours before the race, I could see Peter on the far side of the outer warm up track. He was preparing seriously on his own, so I had to regather myself because I had written the whole thing off.

“I also remember late-morning it was like the man upstairs was unrolling a carpet across the sky. The perimeter of the cloud was ‘unrolled’ in a straight line, which was weird in that it suddenly revealed a clear blue sky. I then set about preparing but never got close to him (Peter). He could see me in the distance, but we never got close or spoke a word about the race beforehand.

“My biggest concern personally was completing the race in order to certify a world record (should it happen), I therefore had to be very careful how I ran the race. I doubted my own staying power.”

With a personal best of just under 47 seconds for the 400m, he knew the first lap of around 50 seconds would be comfortably within his compass.

“I had to run that first lap pretty quickly and once Peter had control of the race, I was happy to grind it out on the second lap to the finish.”

Dashing to the front, Barry executed an ideal first lap of just under 50 seconds – a pace he knew would set Peter up perfectly for an attack on the world record of 1:45.7 held for the previous seven years by Belgian Roger Moens.

“It felt okay but I must admit at the 400m mark, I was starting to feel some discomfort and I thought I’m only halfway through the journey, I have to finish.”

Barry moved to the outside just after the bell to let Peter through – with his primary concern at that stage for himself and not Peter’s ability to deliver a world record.

“Peter had so much ability, so much talent he did not worry me at all. My main worry was myself not being able to finish.”

Running behind the 1960 Olympic 800m champion – who two years later would win the Olympic 800m and 1500m double – was a privilege and Barry had a close-up account of how hard Peter was pushing.

“He was running superbly until just final 200 metre curve,” he explains. “I was well behind him, and it was first time I’d ever witnessed his body wobbling as he guts it out big time over that last 200m. He gave everything he could find in the final straight.”

While Peter played his part, Barry ensured history was made by completing the race in “around 1:56.” He moved to the middle of the track for isolation happy to have played his part in a very special moment in history but was certainly “uncomfortable” from his exertions.

While the Olympic 800m champion celebrated his world record enthusiastically it was only around 20 minutes or so later did Peter head over to Barry to thank him for his pacemaking. “Delirious with joy” at his accomplishment it occurred to the pacemaker, who showed Peter the spoil on his spikes, that the conditions were far from ideal – making Sir Peter’s performance that day at Lancaster Park even more extraordinary.

“I said to Peter ‘I want to tell you something. It is my firm opinion that had you executed the same run that you have just done on a fast, artificial European track rather than the holding, slow track here in Christchurch you would have taken four seconds off the world record.’ He just laughed at me, but I knew from my spikes how damp the track was and while I was sensitive to track the conditions, Peter was just so strong it never seemed an issue.”

Peter went on to add more kudos to his incomparable career in 1964 by completing the Olympic 800m and 1500m double in Tokyo and further lowered his mile record. Yet for many who witnessed his extraordinary race at Lancaster Park many believed it to be his finest race. His world record performance remained the fastest 800m of his career with his next fastest two-lap time of 1:45.1 recorded when winning the Tokyo Olympic title against world-class opposition on a top-quality track.

More than 30 years later on a trip back to New Zealand from his home in the US, Barry and Peter caught up for a coffee to chat about old times. Unprompted Barry recalls, “Peter said, ‘Barry, do you remember what you said to me after my 800m world record?’ I replied, ‘Absolutely, yes, of course but why are asking me all these years later?’ and he said, ‘I now know what you said that day to be correct’.”